A conversation with Karin Olson Hoal, the Wold Family Professor in Environmental Balance for Human Sustainability at Cornell

Karin Olson Hoal has been the Wold Family Professor in Environmental Balance for Human Sustainability at Cornell University since Autumn, 2019. The position was founded with a generous gift from John S. Wold, M.S. ’39 geology. Wold had a long career in various extractive industries and also served a term as Wyoming’s lone Representative in the United States House. The professorship is designed to attract an individual representing the industrial side of sustainable resources who will bring a real-world perspective to students through teaching, mentoring and engagement with academic professors. Olson Hoal will leave Cornell in 2025 to take a six-month Fulbright Distinguished Chair in Science, Technology and Innovation with the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). She sat recently for a Q and A conversation about her career and her time at Cornell. An edited version of this conversation appears below.

What attracted you to the Wold Family Professorship?

I'd been back and forth in industry and academia before coming to Cornell. I enjoy industry because you meet and work with a lot of different people who are not entirely focused on a particular scientific question. This can be really satisfying. Sometimes you want to be able to apply what you know to a real-world problem and that's where people in industry--engineers and business colleagues--come in. And so, when the Wold Family Professor position was advertised, I was very excited to bring those perspectives into such an outstanding institution as Cornell and to a high caliber of students who otherwise may not have been exposed to the resource sector.

At the same time, the resource sector is not a particularly innovative sector of the economy. So it's been really interesting to connect with colleagues in engineering and business, to show them what academic science can offer and to engage, to support innovation and characterization of materials upfront. And now, through these collaborations, it's bringing me toward working more with communities, and with native populations.

Big questions for me now are ‘How we can take the science, link it through the engineering side, and then out to where it really matters, to help people? How can we transform this industry, push toward more sustainable development of resources that views local communities as partners with a huge stake in the process?’

I really enjoy these linkages across a number of areas. As an undergraduate I studied geology and French and music, so I’ve always been somewhat interdisciplinary. The Wold Family Professorship has allowed me to work directly with excellent students and colleagues and to, hopefully, start to bridge some of the gaps between industry, academia, and local communities.

Were you always interested in geology?

I was, but my interest definitely developed and deepened as I got older. I grew up in New Jersey-not far from the city. So we would go into New York often and to the Museum of Natural History where I spent a lot of time looking at the rocks and minerals.

And when I was a kid I had a little rock collection. In the first grade I found a huge (to me) rock and I carried it all the way to school and put it down. And when I did, all these kids started to scream, because seemingly a thousand ants poured out of it. Turns out, it was just a piece of porous road-building aggregate. So I was the girl who brought in the big rock.

In college, in addition to music I was initially going to study biology, but I found that geology was much more interesting and fun. The creative science. I suppose I declared my geology major after being in France and studying music, and talking to a lot of guys who were studying geology. There's quite a famous cohort of geologists from St. Lawrence University from that time, which is where I went to college, and they influenced me quite a bit being just ahead of me. They were going off into the Arctic and flying in helicopters and being dropped down into places that were very remote, and that sounded really great to me. Many of them went to graduate school in Canada, so I went up to McGill for my masters. At that time in particular, you got so much more exposure to the mineral resources sector in Canada. It's a larger part of the economy than in the US. The Canadian students I was with had several years of industry experience under their belts before they even graduated, and many of them have been very successful in their careers, and remain friends. My own field area was in the Ungava peninsula in northern Quebec, two summers isolated, out of communications, with one field assistant in the arctic mapping what was known then as the Cape Smith foldbelt. I’m told they are not allowed to do that to students anymore.

After my master’s from McGill I worked at the New York State Geological Survey for two years, and co-ran a program in the western Adirondacks mapping an enormous area of six 15’ quadrangles with about 13 geologists. At that time the mineral resources and energy sectors hit a major downturn, and so I was fortunate to have that position in Albany.

And then the work we were doing in the Adirondacks led to me wanting to follow up on the mafic rocks and the anorthosite as a Ph.D. At the time, UMass had a large group of researchers doing work in the Adirondacks, so that program was a natural fit for me. I worked with Tony Morse, the leading expert in anorthosites and troctolites, who was a huge influence on me.

After grad school, what were your professional experiences before coming to Cornell for the Wold Family Professorship?

I was invited by Tony Erlank at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, for a Postdoc in mantle metasomatism related to diamonds at the Premier (Cullinan) mine. I loved the diamond industry, and spent altogether six years in southern Africa, and I met my husband in Namibia. I was a project manager for Rio Tinto Namibia for diamond exploration in the Tsumkwe area where we actively engaged with the indigenous !Kung people of northern Namibia and western Botswana. On returning to the US, I was a partner at a consulting service called Corrotoman Geoscience based in Virginia and then Colorado. I then joined Hazen Research, which exposed me to all aspects of minerals process development and where I could see how geological knowledge could really help improve a lot of the engineering—the early days of geomet. I have also worked as a senior consultant with the Australian processing group JK Tech, in Brisbane and Denver. I was ten years as research professor and then center director at the Colorado School of Mines. Along with all of that, for 20 years on and off I have had a consulting LLC where I develop value-based solutions for a more effective minerals industry.

The Wold Family Professorship lasts for one five-year term. As your term nears its end, what do you feel you have accomplished at Cornell?

One thing I am excited about is that we have established a student chapter of the Society of Economic Geologists, which is an international organization of about 7,000 members. There are 105 active student chapters in 32 countries, but there’s never been a chapter of the SEG on the east coast or at an Ivy League school before this one at Cornell. We have a very small chapter, but I think it is positioned well to really take off and thrive. The Cornell students have had field trips, organized critical minerals panels at the Cornell Energy Connection at Cornell Tech, hosted the global student chapter Earth Day symposium, and have generally been really active. They are going to meet with Canadian chapters in a few weeks and have a joint colloquium and field trip. I am really very proud of them.

I think another area I have played a part in here has been getting students to see the opportunities in the mineral resource sector of the economy differently. Instead of just thinking of it as “mining” and dismissing it right away, students are starting to understand that the sector brings in all aspects of geology and exploration, and that understanding the subsurface—the folds and faults and mineral distributions and geochemistry, uses every aspect of earth science to change how minerals are supplied to society. This has been especially exciting for them now in the era of critical minerals, to see what they use, what will be needed in the future, and that earth science will determine how extracting those materials can be done in new, less impactful ways in the future. They see that it’s not just about finding deposits, but more importantly, it's what you do with them. How we can potentially completely change the sector to be less impacting and more sustainable.

And then that, of course, leads students to the idea of “geomet", one of my favorite topics. Geomet combines geological, mining, metallurgical, environmental and economic information to maximize the value of extracted materials for stakeholders while minimizing the risk. Twenty years ago the field really didn't exist, and then a few groups notably in Canada and Australia, but also around the world, developed the fundamental concepts that geological and mineralogical characteristics drive how metals can be extracted. And I was fortunate to be involved at that time as well. The purpose of geomet was to transform how the industry operates. And now, twenty years later, it is so exciting to see how the field has blossomed and developed–there are university positions and departments in geomet, most major companies have their own geomet teams, and we're expanding it further to waste characterization, critical minerals, and communities so that it makes a positive change. I am so excited to see the idea taking root at Cornell.

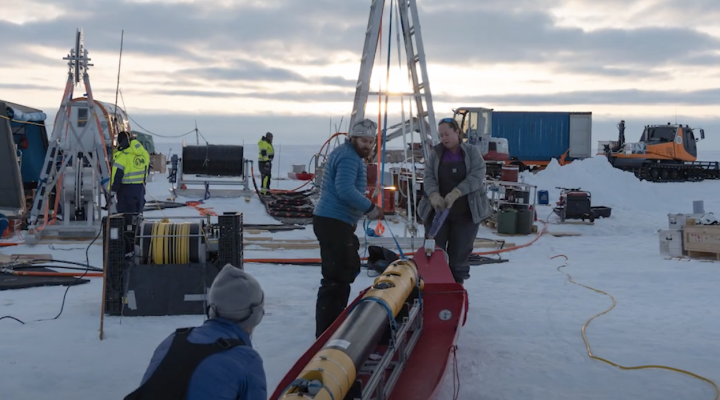

I must say that I am most proud to have worked with some exceptional students while here at Cornell. I have helped supervise five M.Sc. and three M.Eng. students here, in subjects ranging from seafloor nodules to zinc ores, graphite deposits, mineral characterization of the CUBO borehole, and mining’s impact on communities.

What is next for you?

I’ll be at Cornell through the fall semester of 2024 and then I’ll start my Fulbright Distinguished Chair in Science, Technology and Innovation award with the Australian CSIRO in Perth in 2025 for six months. CSIRO is just an amazing, forward-thinking organization. They have state-of-the-art facilities in materials characterization and interesting data-focused technology and brilliant people. Our NSF Convergence Accelerator award in 2023 was in partnership with some of the CSIRO researchers, together with CHESS here at Cornell. And they have real funding for making real change to the mineral resource sector. They have a very interesting model in Australia with industry, government, and academic partnerships to solve particular major challenges, and that would be a great model to emulate here in the US. I hope to be working with one CRC that is looking at the transitions in mining and mineral economies, working with aboriginal and mining collaborators and academia to see how we can solve some of these resource challenges.

I do look forward to staying in touch and involved with my Cornell partners as we move forward, and seeing how we can really make positive change. I am sure the students I have seen here will do some really great things in the future!