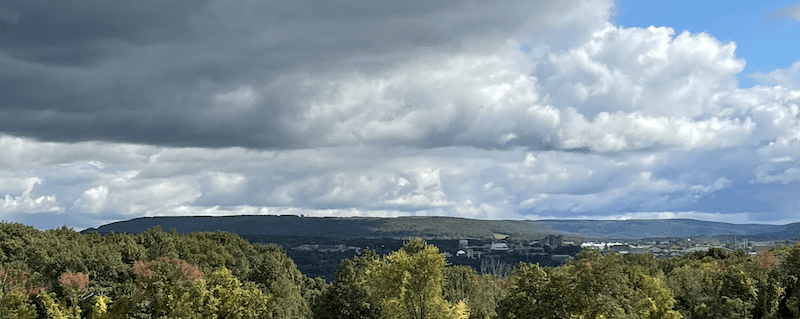

Understanding the Past and Present to Guide the Future

To improve the quality of life for everyone on this planet, we must first understand the complexities of our natural systems and the impact of human behavior on the natural balance. The Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell embraces this mission through exceptional teaching, world-class research, and committed service and outreach.

Our Programs

News Highlights

-

Earth’s inner core is less solid than previously thought

The surface of the Earth’s inner core may be changing, according to a new study from scientists that detected structural changes near the planet’s center.

-

Don Turcotte, professor emeritus, tectonics pioneer, dies at 92

Don Turcotte, the former Maxwell Upson Professor of Engineering in the Department of Geological Sciences who brought his aeronautic research roots into pioneering collaborations in the study of mantle dynamics and plate tectonics, died Feb. 4 in Davis, California.

-

Geologists to visit, study active Chilean volcano

Cornell geologists will deploy monitoring equipment at the remote and active Cordón Caulle volcano in Chile, a site that remained dormant for more than 50 years before erupting in 2011.

-

Cornell fills data gap for volcanic ash effects on Earth systems

To bridge the data gap between volcanologists and atmospheric scientists, Cornell researchers have depicted volcanic ash samples to learn how this tiny dust plays a big climate role.

Alumni Profiles

-

Finding creative solutions and protecting the environment – Jonathan Kimchi ’10

Eighteen years ago, Jonathan Kimchi ’10 was a first-year Cornell student who knew he wanted to make an impact on the environment by combining his passions for water resources and engineering. These days, he is realizing that goal as the…

-

A visceral sense of the land – Peter Flemings Ph.D. ’90

In the more than 30 years since Peter Flemings Ph.D. ’90 left Cornell with his Geology doctorate in hand, he has been engaged in research at some of the nation’s premier academic institutions, including the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, MIT, Penn…

-

EAS alum is using data to improve mining practices – Hannah Lang ’18

Hannah Lang ’18 has never been a rock collector and would definitely not refer to herself as a “rock nerd,” (though some of her good friends are). Yet, she graduated from Cornell EAS with a B.A. in the science of…

Strategic Research Areas

-

![Desert location with four people in the foreground and mountains in the background.]()

Climate and Paleoclimate

Study of Earth’s climate extends from investigation of past climate states, to investigation of the key underlying physical and chemical controls on modern climate balances, to prediction of the climate outcomes of ongoing anthropogenic and natural forcings.

-

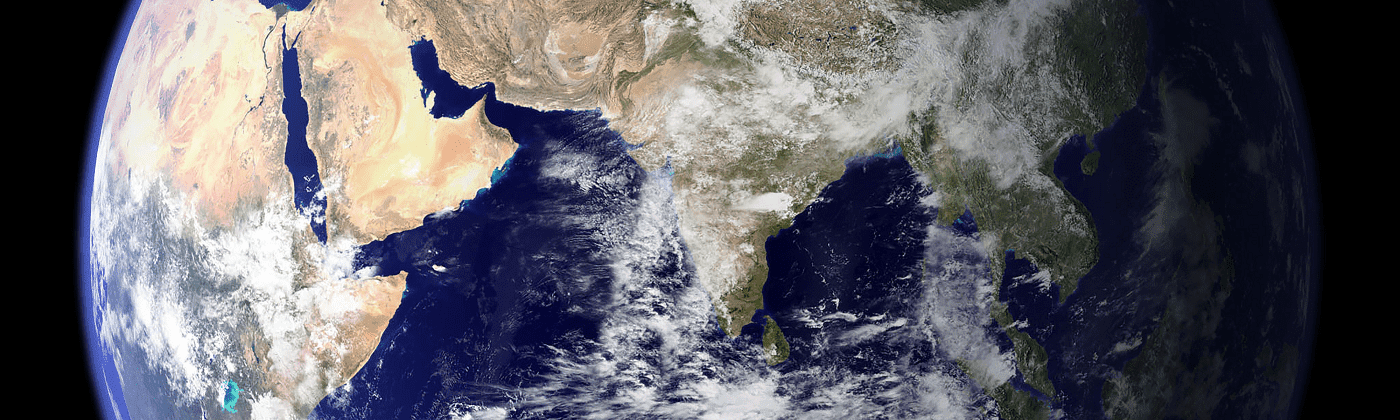

![Earth as seen from space, with India centered.]()

Earth System Science

Earth system science spans knowledge across the lithosphere, biosphere, atmosphere, cryosphere and hydrosphere. Earth system science is intellectually interesting, as it seeks to understand the world around us, as well as relevant for solving problems relating to energy, climate and pollution.

-

![Steaming thermal pool in New Zealand]()

Energy, Mineral, and Water Resources

We make society aware of energy’s indirect role in our lives: for example, modern food production requires massive amounts of energy for fertilizer, harvest, and transportation to market.

-

![steaming top of a conical volcano]()

Geochemistry, Petrology, and Volcanology

This area of research focuses on the study of the chemical composition of the earth and its rocks and minerals.

-

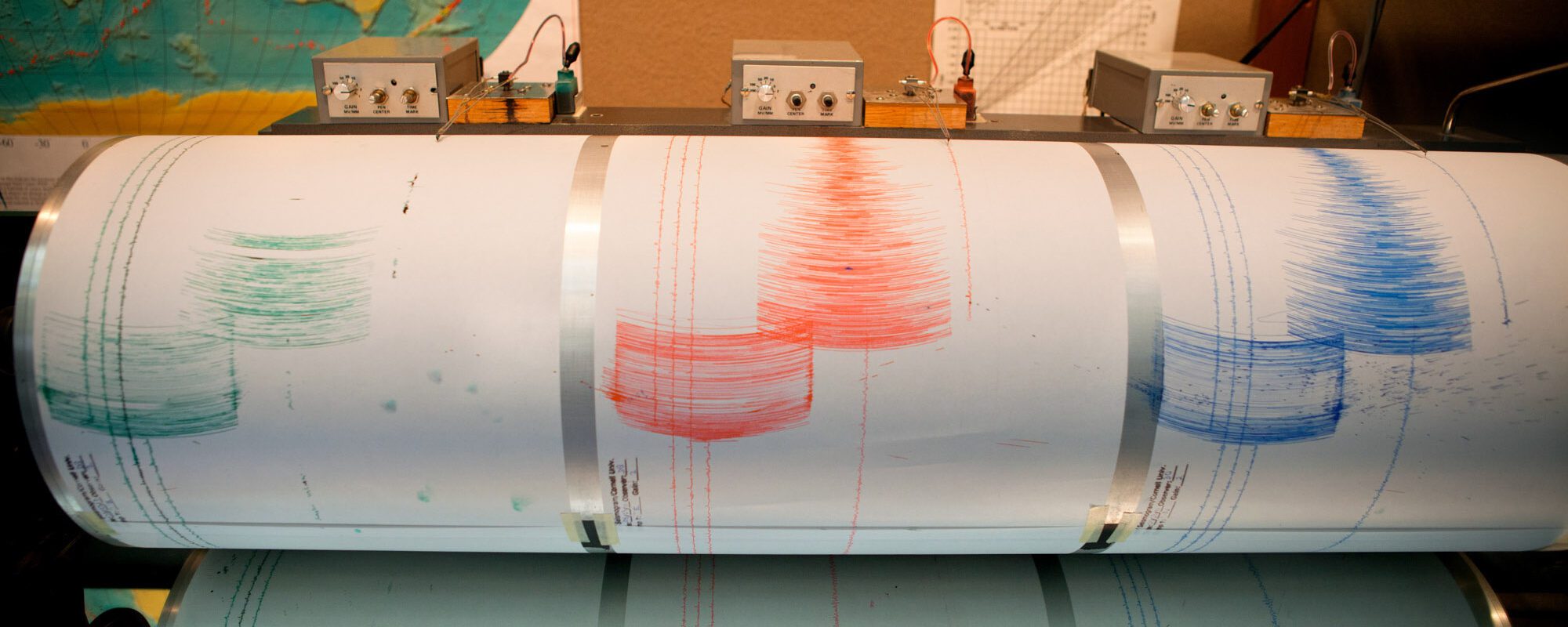

![person sitting in a hole, wiring a seismic sensor.]()

Geophysics and Seismology

This area of research concerns itself with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis.

-

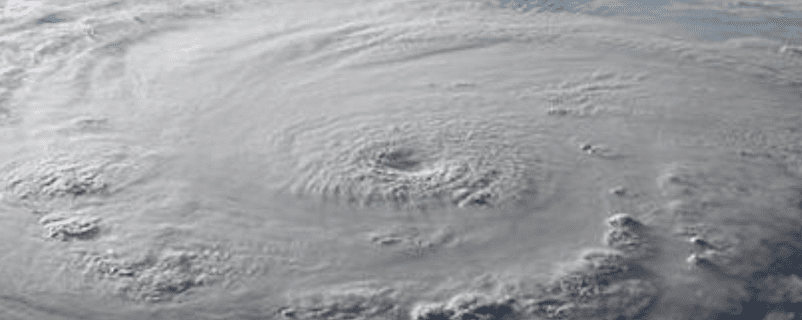

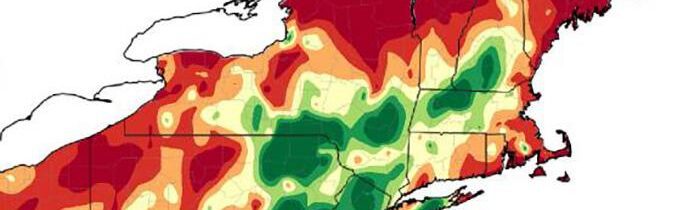

![climate map of part of the Northeastern United States]()

Meteorology and Applied Climatology

Established in 1983, the Northeast Regional Climate Center (NRCC) is located in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell University.

-

![Overhead view of waves crashing on a sandy shore]()

Ocean Sciences

Research includes Marine Ecosystem Research in the North Atlantic (MERRCINA), Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) L, Near-Real-Time Modeling of Right Whale Foraging Areas in the Gulf of Maine and Interannual Variability of North Atlantic Spring Phytoplankton Blooms in the North Atlantic.

-

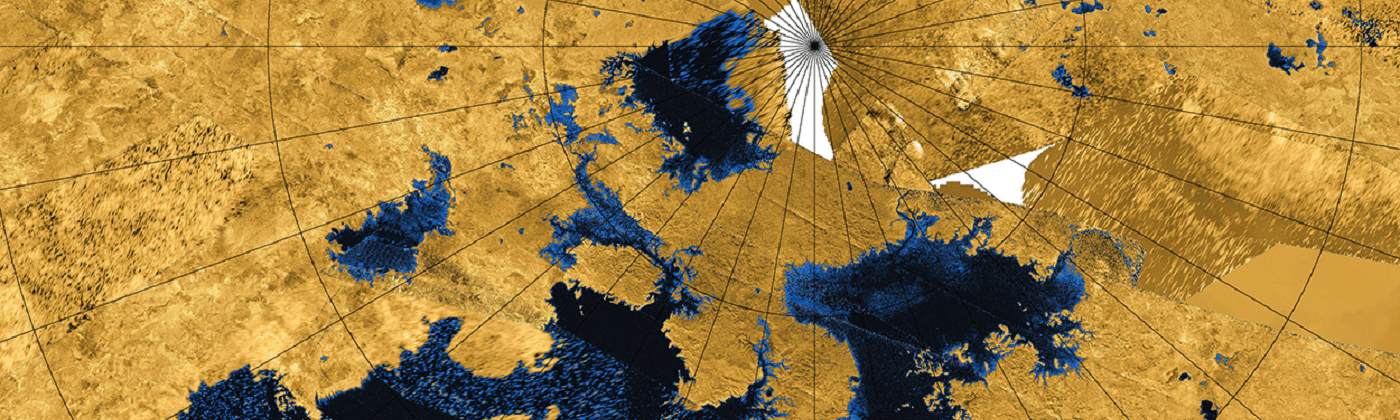

![satellite image of the North polar lakes and seas of Titan.]()

Space and Planetary Sciences

Research in space and planetary sciences spans many disciplines and four departments at Cornell, including the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.